People who are miserable in their 70s all made these 10 same mistakes in their 50s and 60s

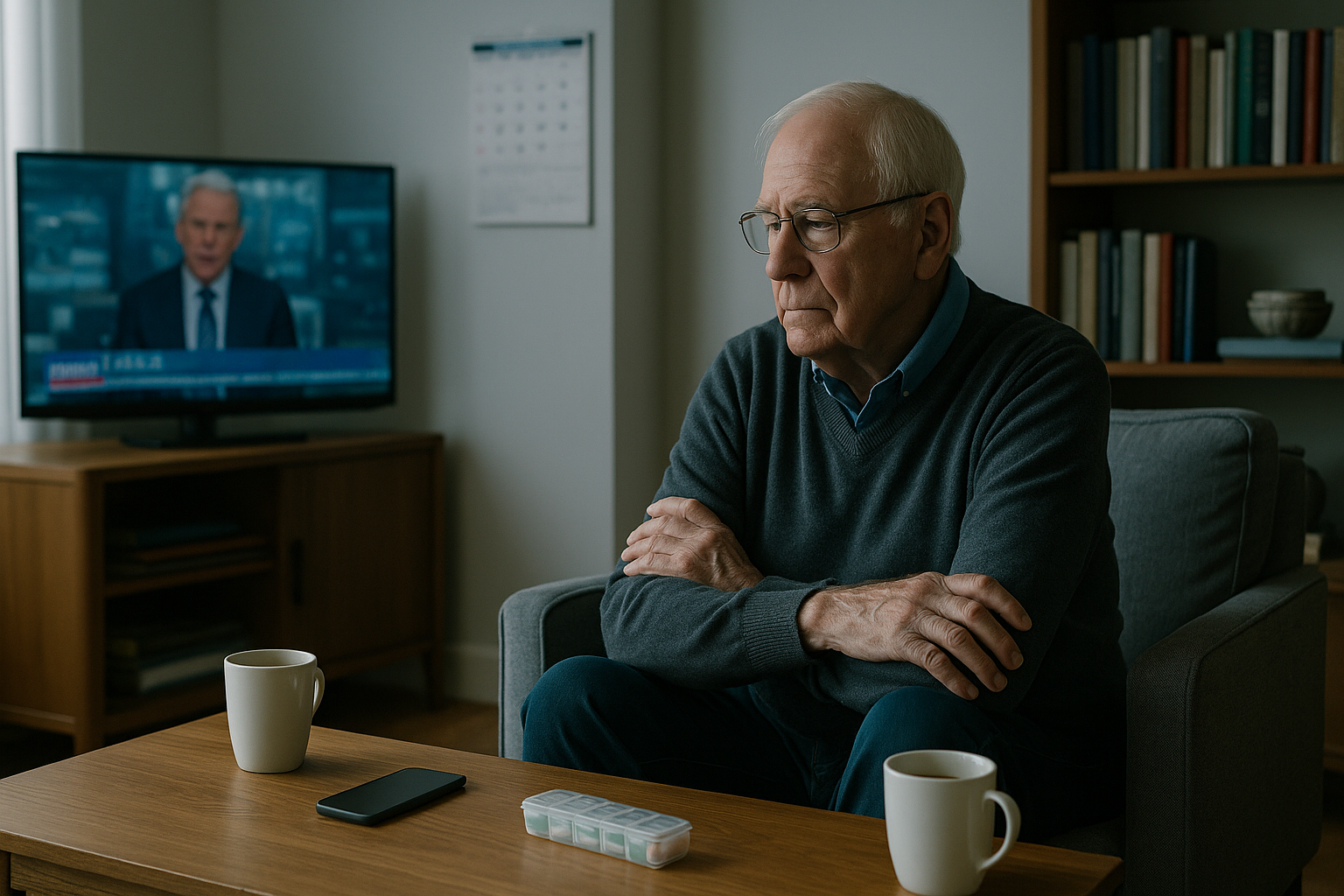

At 72, Robert sits in his pristine living room, CNN on mute, fourth coffee going cold, waiting for nothing in particular. His calendar is empty except for doctor’s appointments. His phone rarely rings. His retirement, which he’d imagined as freedom, feels like house arrest. “I don’t know how this happened,” he tells me, but that’s not quite true. The seeds of his current misery were planted in his sixties, when he still had time to course-correct but didn’t realize he needed to.

The sixties are the decade of invisible consequences. You’re still young enough to feel immortal, old enough to think you’ve earned the right to coast. The choices you make—or don’t make—compound quietly, revealing themselves only when it’s too late to undo them.

1. They let their bodies decline “gradually”

“I’ll start exercising when I retire.” “I’ll eat better after the holidays.” The sixties are full of tomorrow promises while the body keeps today’s score. They gained “just” five pounds a year, lost “a little” flexibility, got winded “slightly” easier.

By 70, those gradual declines become cliffs. The knee that was stiff is now immobile. The extra weight is now diabetes. The shortness of breath is now cardiac disease. Muscle mass loss accelerates after 60—what you don’t actively maintain, you rapidly lose.

2. They assumed friendships would maintain themselves

Work friends would stay close after retirement. Couple friends would remain after divorce or death. Neighborhood friends would always be there. They made no effort to actively cultivate friendships, assuming proximity was enough.

Now they sit alone, scrolling through Facebook, seeing lives they’re no longer part of. Friendship in later life requires intention—regular calls, planned gatherings, deliberate maintenance. Those who treated friendship as automatic in their 60s find themselves friendless in their 70s.

3. They never developed interests beyond work

Their identity was “Senior Vice President” or “Regional Manager.” Hobbies were what other people had. Passion projects were for retirement, someday, eventually. They spent their 60s doing victory laps of careers instead of planting seeds for what came next.

Retirement arrives and they’re lost. No routine, no purpose, no idea how to fill sixteen waking hours. The psychological adjustment from career to retirement is brutal for those who never developed alternate identities.

4. They stopped learning new things

“I’m too old for that” became their motto. Too old for technology, new music, changing perspectives. They chose familiar over novel, comfortable over challenging. Their world shrunk to the size of their comfort zone.

The brain needs novelty like muscles need resistance. Those who stopped learning in their 60s find their cognitive flexibility gone in their 70s. They can’t adapt to change because they stopped practicing adaptation when they still could.

5. They ignored their marriage (or their singleness)

Couples coasted on autopilot, assuming forty years of marriage would carry them through. Singles assumed they were fine alone, making no effort to date or connect. Both groups treated their relationship status as fixed rather than requiring attention.

Now coupled 70-somethings are strangers sharing space, while single ones face acute loneliness. Relationship satisfactionin later life requires active cultivation, whether maintaining a marriage or building new connections.

6. They burned bridges with family

“They know where to find me” was their position on estranged children. “I’m done trying” was their stance on difficult siblings. They stood on principle while relationships withered, choosing rightness over reconciliation.

In their 70s, they wonder why no one visits, why grandchildren are strangers, why holidays are quiet. Pride makes poor company. The bridges burned in your 60s can’t be rebuilt when you need to cross them in your 70s.

7. They put off health screenings and maintenance

The colonoscopy could wait another year. The hearing aids were for “really” deaf people. The mental health support was for weak people. They treated their body like a car they planned to trade in, not the only vehicle they’d ever have.

Small problems became big ones. Treatable conditions became chronic ones. Manageable issues became life-limiting ones. Preventive care in the 60s determines quality of life in the 70s, but they learned this through suffering rather than wisdom.

8. They resisted adapting their living situation

The four-bedroom house made sense when kids visited. The two-story layout was fine when knees worked. The suburban location was perfect when they could drive. They refused to downsize, relocate, or modify, treating change as defeat.

Now they’re trapped in houses that don’t work for their bodies, in locations that ensure isolation, maintaining spaces that exhaust them. The living situations that worked at 60 become prisons at 75.

9. They avoided planning for decline

Wills were for old people. Long-term care insurance was pessimistic. Advance directives were morbid. They avoided every conversation and document that acknowledged mortality, as if ignoring aging would prevent it.

Now they’re in crisis with no plan. Their children fight over decisions. Their savings evaporate in care costs. Their wishes are unknown because they never voiced them. The planning avoided in the 60s becomes the chaos of the 70s.

10. They chose isolation over vulnerability

Asking for help was weakness. Admitting struggle was failure. Showing need was shameful. They presented strength while dying inside, choosing isolation over the vulnerability of connection.

In their 70s, when they finally need help, no one knows to offer it. They’ve trained everyone to see them as self-sufficient. The independence they performed in their 60s becomes the abandonment they experience in their 70s.

Final thoughts

Robert’s misery at 72 wasn’t inevitable—it was constructed through a thousand small choices in his 60s. Each “tomorrow” that never came, each connection allowed to atrophy, each adaptation refused. The tragedy isn’t that he’s miserable now; it’s that he had a decade to prevent it and didn’t know it mattered.

The 60s are the decade when you’re writing the story of your 70s, but you don’t realize you’re holding the pen. Every choice to maintain or neglect, to connect or isolate, to grow or stagnate is authoring your future experience. The miserable 70-somethings aren’t victims of aging—they’re living the consequences of choices made when different choices were still possible.

If you’re in your 60s, look at Robert and see your potential future. Then do everything differently.